Zika Virus: What You Need to Know

In the United States, awareness and concern for Zika virus reached new heights in August 2016 when 21 cases of the Zika virus were contracted through mosquitoes near Miami, marking the first such cases in the United States. This prompted the CDC to issue an unprecedented travel advisory within the country, warning pregnant women and their partners to avoid travel to the affected neighborhood.

In 2017, the number of reported Zika cases in the United States began to decline. Since 2018, there have been no reports of Zika virus transmission by mosquitoes in the continental United States, and since 2019, no confirmed Zika cases have been reported from U.S. territories.

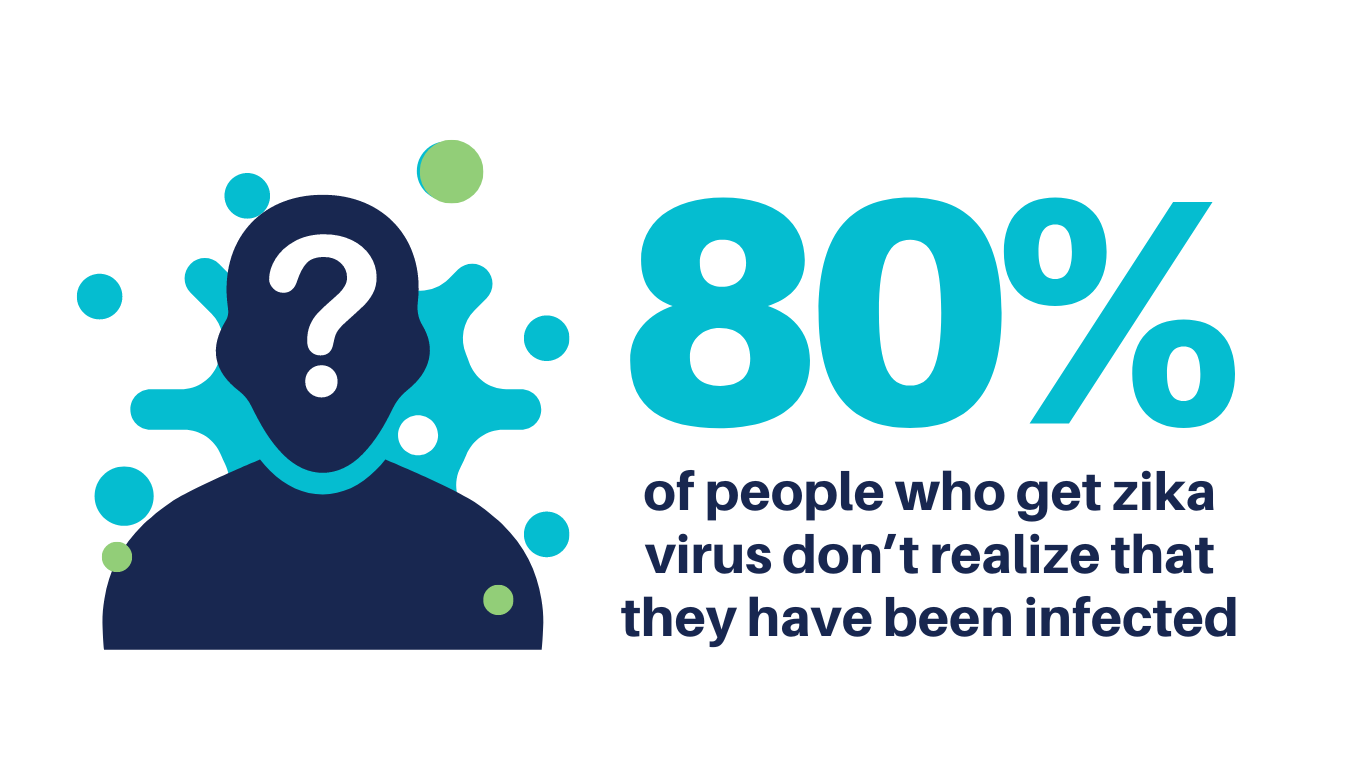

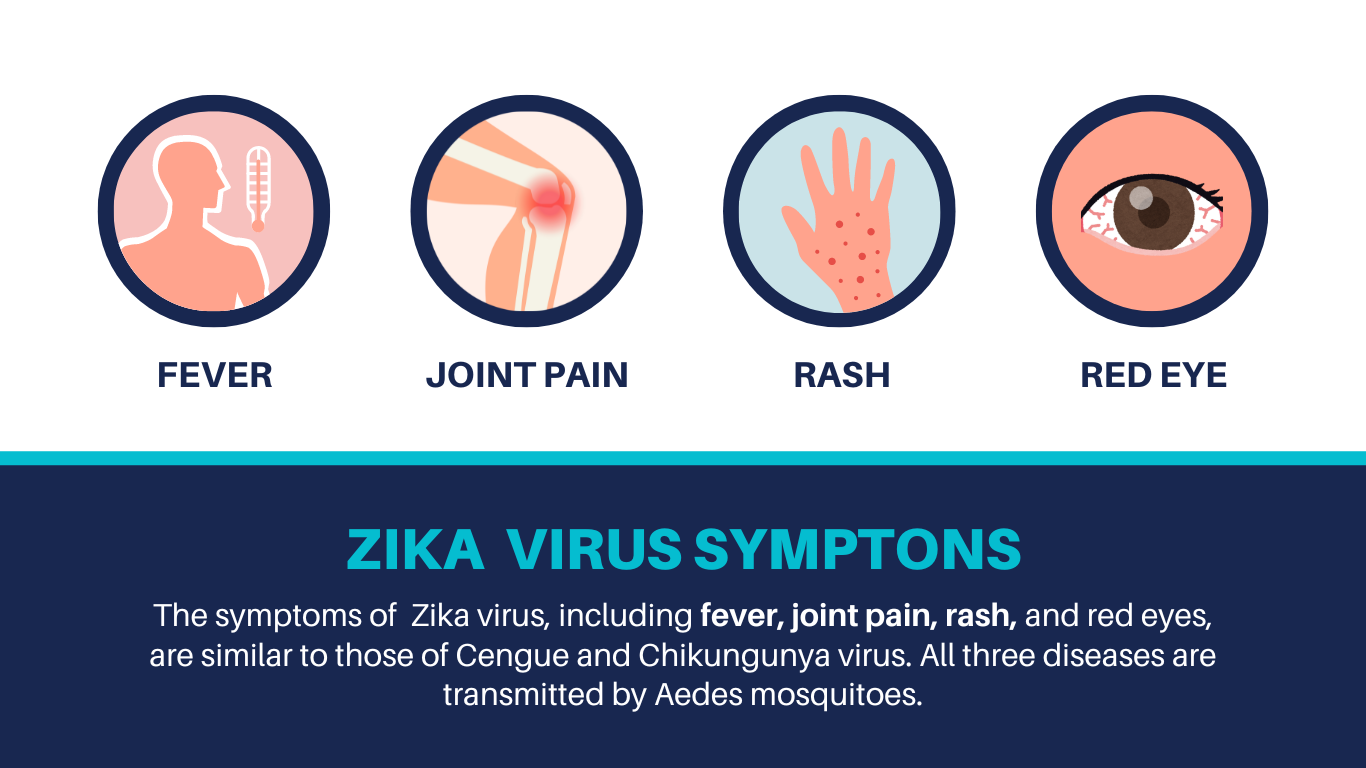

- Zika is a virus primarily spread through the bite of an infected mosquito, with symptoms the CDC describes as fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (red eyes). Symptoms are seldom severe enough to require hospitalization, and the disease rarely results in death.

- There is a confirmed link between Zika and serious birth defects associated with pregnant women who have become infected, most commonly found through cases of microcephaly. This condition results in the child being born with a smaller-than-average head size, interfering with brain development.

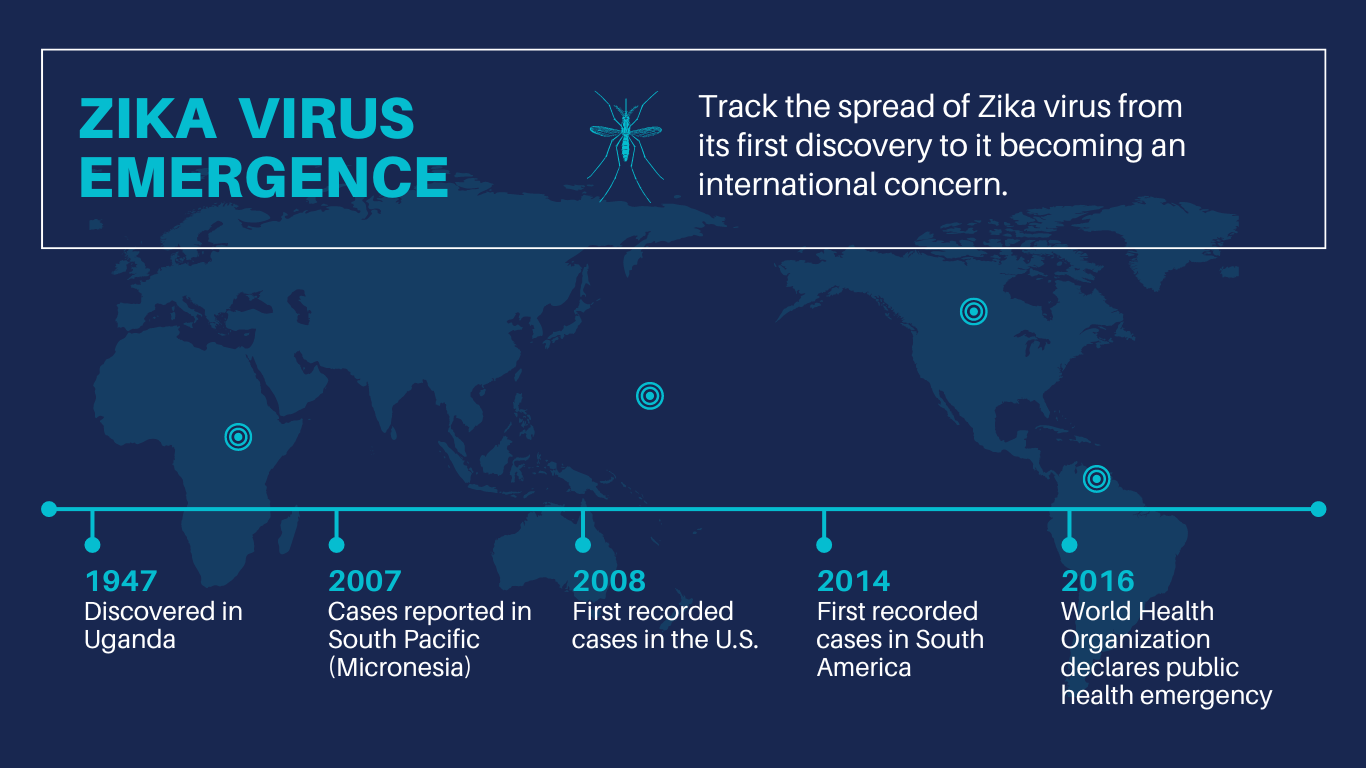

- The Zika virus was first discovered in 1947, but cases were rarely reported in the 60 years that followed. From 2007-2014, sporadic outbreaks were identified in areas of Asia, Africa and the Pacific islands.

- The most severe outbreak was reported in Brazil when more than 7,000 adult cases were identified between February and April 2015. By January 2016, the country reported nearly 4,000 suspected cases of microcephaly.

- By August 2016, more than 60 countries had identified locally-acquired cases of Zika.

Aedes aegypti – the vector:

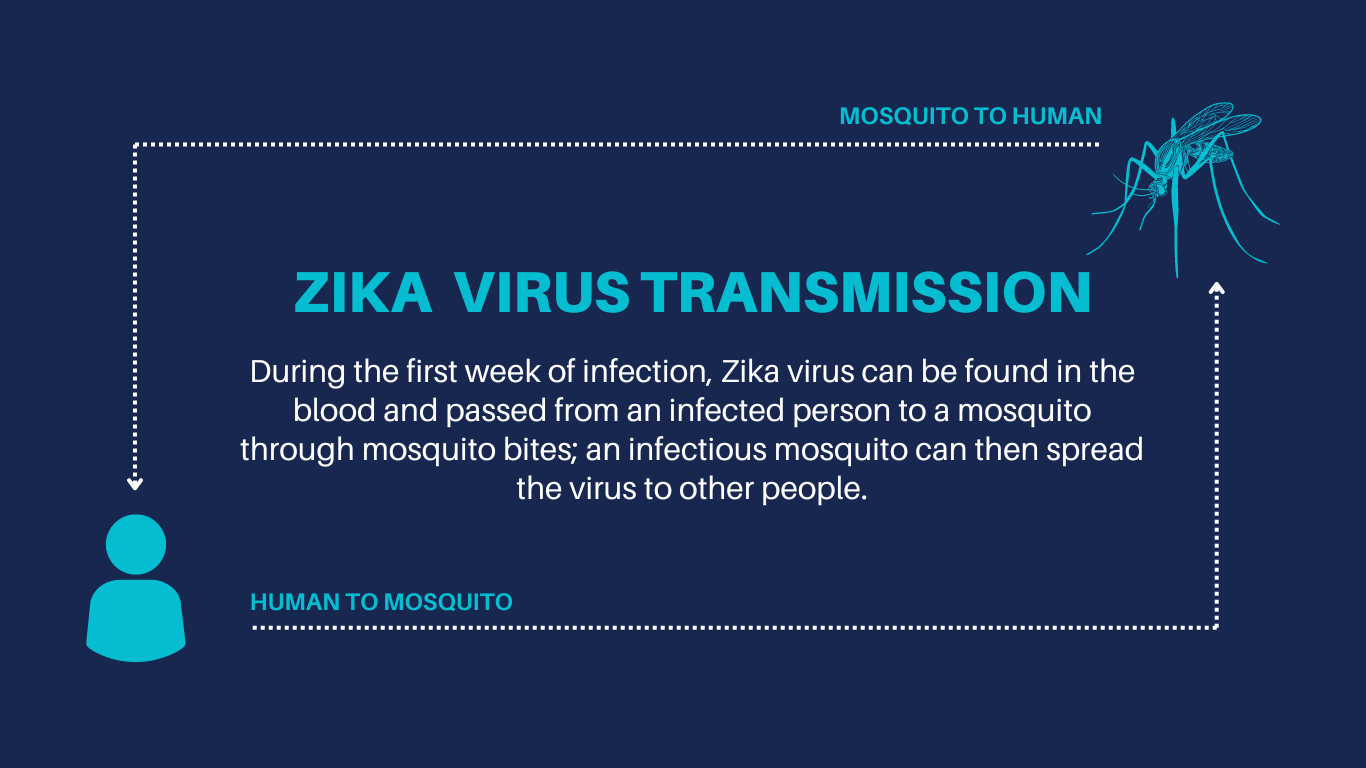

- The Zika virus is known to be spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito species, a known vector of several diseases including the dengue virus, yellow fever virus, and chikungunya virus.

- This mosquito primarily feeds on humans and is typically found in densely populated urban areas.

- Aedes aegypti mosquitoes prefer to breed in small containers of clean water, in both indoor and outdoor locations close to humans.

- The species is most active during the day, typically biting within two hours after sunrise and two hours before sunset.

What can the general public do?

Effective mosquito control requires contributions from the entire community, beyond just the professionals dedicated to controlling the pests. Daniel Markowski, PhD technical advisor for the American Mosquito Control Association, recommends the general public follow the “Three D’s” for effective prevention:

- Drain standing water wherever possible. This includes outdoor containers – such as old tires, buckets, gutters and pool covers – and indoor containers such as potted plants, pet water bowls and even refrigerator water collection trays.

- Dress properly, including long sleeves and long pants to minimize skin exposure. Loosely fitting clothing is recommended as mosquitoes can potentially feed through tight clothing.

- Defend against mosquitoes with an EPA-registered repellent.

Additionally, citizens are advised to contact their local Mosquito Abatement District or Public Health Officials to report mosquito activity and request services in their area. This contact information and more household tips can be found at www.mosquito-awareness.com.

The Zika virus is likely to continue garnering attention, but mosquito abatement districts and public health officials remain committed to protecting communities from all mosquito-borne diseases. The best way to protect communities and limit these nuisance and disease carrying pests is through proactive control measures from mosquito control professionals. Central Life Sciences offers a broad line of Altosid®, FourStar® and Duplex-G® larvicides as well as Zenivex®, Perm-X® and Pyronyl™ adulticides that can help with any integrated mosquito control program.

For more information, contact a representative near you.